These Who Worry Illness Most Are Most More likely to Choose Authoritarian Regimes - The Shepherd of the Hills Gazette

These Who Worry Illness Most Are Most More likely to Choose Authoritarian Regimes - The Shepherd of the Hills Gazette |

| Posted: 24 Nov 2020 03:44 PM PST Covid-19 has unleashed a pandemic of restrictive measures on the population. Lockdowns and mask mandates are becoming widespread. Libertarians have been vociferously denouncing covid-19 containment strategies as draconian. Evolutionary psychologists, however, argue that reactions in favor of government restrictions are the norm in environments where the public fears contamination. According to the parasitic stress theory popularized by Randy Thornhill and Corey Fincher, societies with a high prevalence of diseases are more supportive of authoritarian policies. This is unsurprising because to prevent transmissions experts often recommend limiting movement. Due to fear, citizens would have a vested interest in promoting policies claiming to lower infections. Likewise, the aversion to contracting covid-19 has forced many to advocate hysterical policies. For anthropologists interested in analyzing the parasitic stress theory, covid-19 is a perfect case study. Murray, Schaller, and Suedfeld (2013) in their discussion of the relationship between pathogens and authoritarianism elucidate the importance of disease control mechanisms in germ-rich societies. "Because many disease-causing parasites are invisible, and their actions mysterious, disease control has historically depended substantially on adherence to ritualized behavioral practices that reduced infection risk. Individuals who openly dissented from, or simply failed to conform to, these behavioral traditions, therefore, posed a health threat to self and others." Unfortunately, as covid-19 has demonstrated, people are willing to subject themselves to rituals even if they have no discernible impact on deterring transmissions. One must appear to be complying with the crowd or face expulsion. Humans are emotional creatures, and hence they give primacy to symbolic gestures. For example, recently researchers noted that "no direct evidence indicates that public mask wearing protects either the wearer or others." Yet despite the dearth of evidence in favor of wearing masks, the researchers nevertheless advocated their use in the name of group solidarity: "Given the severity of this pandemic and the difficulty of control…we suggest appealing to altruism and the need to protect others." Blind conformity to public opinion is also evident when analysts recommend mask mandates after admitting that they "may be far from enough to prevent an increase in new infections." Although the evidence does not support containment measures such as mask mandates and lockdowns, they remain quite popular among the intelligentsia. However, this pattern is consistent with the parasitic stress theory. To some, the costs of tolerating dissent in an environment compatible with diseases are too onerous, so contrarians are usually viewed as a threat to society. Therefore, in the era of covid-19 ideas in opposition to the prevailing orthodoxy will be neutered. For instance, writing in The Spectator, Fraser Myers exposes Google for censoring the Great Barrington Declaration: The Great Barrington Declaration was spearheaded by Martin Kulldorff from Harvard Medical School, Sunetra Gupta from Oxford University and Jay Bhattacharya from Stanford University Medical School. The declaration was bound to cause controversy for going against the global political consensus, which holds that lockdowns are key to minimising mortality from Covid-19. Instead, the signatories argue that younger people, who face minimal risk from the virus, should be able to go about their lives unimpeded, while resources are devoted to protecting the most vulnerable. But for making this argument, the declaration has been censored. Tech giant Google has decided that the view of these scientists should be covered up. Most users in English-speaking countries, when they google 'Great Barrington Declaration', will not be directed to the declaration itself but to articles that are critical of the declaration—and some that amount to little more than smears of the signatories. Moreover, numerous examples suggest that covid-19 is being leveraged as a justification for authoritarianism. Consider the insightful observation of Steven Simon in an article for the journal Survival: In illuminating COVID-19's utility for power-grabbers, observers have tended to point to three cases: Israel, Hungary and the Philippines. In Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been accused of manipulating pandemic fears to delay his prosecution on corruption charges by shuttering the courts, hamstringing his centrist opponent, Benjamin Gantz, and intensifying electronic surveillance of Israeli society. In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has cited the crisis to extract from a right-leaning legislature remarkably broad powers to suppress dissent. And in the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte, after mishandling the response to the pandemic, has moved to quash criticism and harshly imposed quarantine and curfew rules, ordering that violators be shot dead. Similarly, as Zmigrod et al. (2020) remind us, the changes wrought by pandemics are often long term: "Historical pathogen prevalence still predicts contemporary ideological attitudes, and so if Covid-19 elevates the allure of authoritarian ideologies, the effects could be long-lasting." Covid-19 has nurtured authoritarian sentiments, and the residues will remain long after we have discovered a vaccine. Based on the present environment, measures may become more stringent. Therefore, the only option available to proponents of liberty is to be a bulwark against tyranny by strongly opposing the violations of human rights in the name of preventing covid-19. |

| How Do Pandemics End? History Suggests Diseases Fade But Are Almost Never Truly Gone - Snopes.com Posted: 25 Nov 2020 09:13 AM PST This article is republished here with permission from The Conversation. This content is shared here because the topic may interest Snopes readers; it does not, however, represent the work of Snopes fact-checkers or editors. When will the pandemic end? All these months in, with over 60 million COVID-19 cases and more than 1.4 million deaths globally, you may be wondering, with increasing exasperation, how long this will continue. Since the beginning of the pandemic, epidemiologists and public health specialists have been using mathematical models to forecast the future in an effort to curb the coronvirus's spread. But infectious disease modeling is tricky. Epidemiologists warn that "[m]odels are not crystal balls," and even sophisticated versions, like those that combine forecasts or use machine learning, can't necessarily reveal when the pandemic will end or how many people will die. As a historian who studies disease and public health, I suggest that instead of looking forward for clues, you can look back to see what brought past outbreaks to a close – or didn't.

Jeff Greenberg/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Where we are now in the course of the pandemicIn the early days of the pandemic, many people hoped the coronavirus would simply fade away. Some argued that it would disappear on its own with the summer heat. Others claimed that herd immunity would kick in once enough people had been infected. But none of that has happened. A combination of public health efforts to contain and mitigate the pandemic – from rigorous testing and contact tracing to social distancing and wearing masks – have been proven to help. Given that the virus has spread almost everywhere in the world, though, such measures alone can't bring the pandemic to an end. All eyes are now turned to vaccine development, which is being pursued at unprecedented speed. Yet experts tell us that even with a successful vaccine and effective treatment, COVID-19 may never go away. Even if the pandemic is curbed in one part of the world, it will likely continue in other places, causing infections elsewhere. And even if it is no longer an immediate pandemic-level threat, the coronavirus will likely become endemic – meaning slow, sustained transmission will persist. The coronavirus will continue to cause smaller outbreaks, much like seasonal flu. The history of pandemics is full of such frustrating examples. Once they emerge, diseases rarely leaveWhether bacterial, viral or parasitic, virtually every disease pathogen that has affected people over the last several thousand years is still with us, because it is nearly impossible to fully eradicate them. The only disease that has been eradicated through vaccination is smallpox. Mass vaccination campaigns led by the World Health Organization in the 1960s and 1970s were successful, and in 1980, smallpox was declared the first – and still, the only – human disease to be fully eradicated.

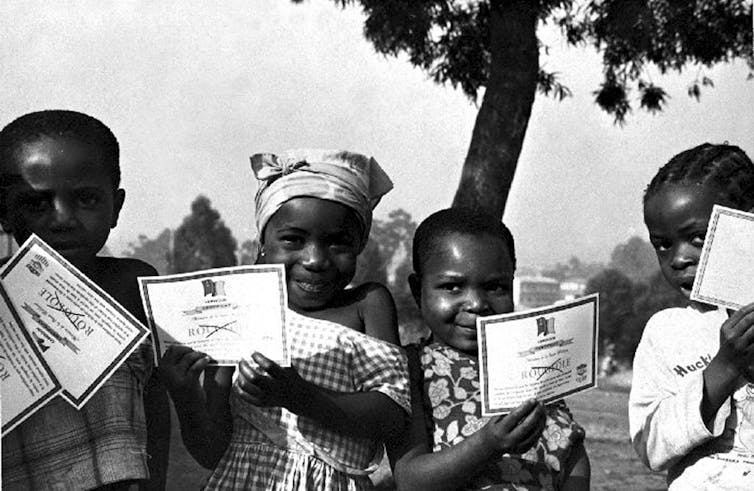

Smith Collection/Gado via Getty Images So success stories like smallpox are exceptional. It is rather the rule that diseases come to stay. Take, for example, pathogens like malaria. Transmitted via parasite, it's almost as old as humanity and still exacts a heavy disease burden today: There were about 228 million malaria cases and 405,000 deaths worldwide in 2018. Since 1955, global programs to eradicate malaria, assisted by the use of DDT and chloroquine, brought some success, but the disease is still endemic in many countries of the Global South. Similarly, diseases such as tuberculosis, leprosy and measles have been with us for several millennia. And despite all efforts, immediate eradication is still not in sight. Add to this mix relatively younger pathogens, such as HIV and Ebola virus, along with influenza and coronaviruses including SARS, MERS and SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19, and the overall epidemiological picture becomes clear. Research on the global burden of disease finds that annual mortality caused by infectious diseases – most of which occurs in the developing world – is nearly one-third of all deaths globally. Today, in an age of global air travel, climate change and ecological disturbances, we are constantly exposed to the threat of emerging infectious diseases while continuing to suffer from much older diseases that remain alive and well. Once added to the repertoire of pathogens that affect human societies, most infectious diseases are here to stay. Plague caused past pandemics – and still pops upEven infections that now have effective vaccines and treatments continue to take lives. Perhaps no disease can help illustrate this point better than plague, the single most deadly infectious disease in human history. Its name continues to be synonymous with horror even today.

AP Photo/Francesco Bellini Plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. There have been countless local outbreaks and at least three documented plague pandemics over the last 5,000 years, killing hundreds of millions of people. The most notorious of all pandemics was the Black Death of the mid-14th century. Yet the Black Death was far from being an isolated outburst. Plague returned every decade or even more frequently, each time hitting already weakened societies and taking its toll during at least six centuries. Even before the sanitary revolution of the 19th century, each outbreak gradually died down over the course of months and sometimes years as a result of changes in temperature, humidity and the availability of hosts, vectors and a sufficient number of susceptible individuals. Some societies recovered relatively quickly from their losses caused by the Black Death. Others never did. For example, medieval Egypt could not fully recover from the lingering effects of the pandemic, which particularly devastated its agricultural sector. The cumulative effects of declining populations became impossible to recoup. It led to the gradual decline of the Mamluk Sultanate and its conquest by the Ottomans within less than two centuries. That very same state-wrecking plague bacterium remains with us even today, a reminder of the very long persistence and resilience of pathogens. Hopefully COVID-19 will not persist for millennia. But until there's a successful vaccine, and likely even after, no one is safe. Politics here are crucial: When vaccination programs are weakened, infections can come roaring back. Just look at measles and polio, which resurge as soon as vaccination efforts falter. Given such historical and contemporary precedents, humanity can only hope that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 will prove to be a tractable and eradicable pathogen. But the history of pandemics teaches us to expect otherwise. Nükhet Varlik, Associate Professor of History, University of South Carolina This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "parasitic diseases examples" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment