Chagas disease: Research shows stronger but less frequent drug doses could be key to cure - Outbreak News Today

Chagas disease: Research shows stronger but less frequent drug doses could be key to cure - Outbreak News Today |

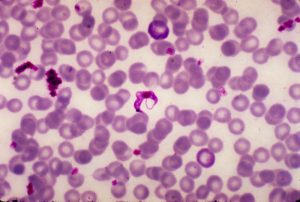

| Posted: 31 Oct 2020 04:58 AM PDT By NewsDesk @bactiman63 Researchers in the University of Georgia's Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases have found that a more intensive, less frequent drug regimen with currently available therapeutics could cure the infection that causes Chagas disease, a potentially life-threatening illness affecting up to 300,000 people in the United States.  Trypanosoma cruzi is a single-celled parasitic organism that causes Chagas disease. At least 6 million people are infected by T. cruzi, mostly in South America. Current drug therapies have been ineffective in completely clearing the infection and are associated with severe adverse side effects. A single dose of benznidazole has been shown to be highly effective in killing more than 90% of parasites. However, after a CTEGD team found some of the parasites enter into a dormancy stage, the researchers hypothesized that an intermittent treatment schedule could be effective. "In this system we can see what a single dose of drug does," said Rick Tarleton, Regents' Professor in UGA's department of cellular biology. "Does it make sense to give a drug twice daily when the remaining dormant parasites are insensitive to it?" Texas: Wichita Falls reports 'rare' Trypanosoma cruzi positive kissing bug The investigators found that giving as little as two-and-a-half times the typical daily dose of benznidazole, once per week for 30 weeks, completely cleared the infection, whereas giving the standard daily dose once a week for a longer period did not. "Current human trials are only looking at giving lower doses over a shorter time period, which is the exact opposite of what we show works," said Tarleton. Since Tarleton's team worked with a mouse model, how this change in treatment regimen will translate in humans is yet unknown, as are any potential side effects of the higher doses. Adverse reactions already are a problem with current treatments; the hope is that side effects from a less frequent dosage would be more tolerable. Assessing the success of treatments in Chagas disease is a significant challenge. Tissue samples from infected organisms might not be representative of the entire organ or animal, since low numbers of persistent, dormant parasites can be difficult to detect. Therefore, Tarleton's group used light sheet fluorescence microscopy to view intact whole organs from infected mice. "With light sheet fluorescence microscopy, you have a broad view of potentially any tissue in the mouse that allows for dependable assessment of parasite load and persistence," said Tarleton. "It gives you an incredible view of the infection." Using this technology, they learned something new about the dormant parasites: Some were still susceptible to drug treatment. This provides hope that new drug therapies could be developed to target these parasites. "Discovery of new drugs should continue," Tarleton said. "We still need better drugs." |

| Lethal skin disease finds possible safer vaccine in combining new with old - OSU - The Lantern Posted: 08 Oct 2020 12:00 AM PDT   3D illustration of the Leishmania parasite which causes leishmaniasis. Credit Kateryna Kon via Shutterstock Researchers at Ohio State and other universities are bringing together old practices and new technology to fight a parasitic skin disease. Combining inoculation and gene-editing, the approach introduces a genetically weakened Leishmania parasite into the body to possibly serve as a safer vaccine against leishmaniasis, a skin disease that causes boils, sores and scars around the body, nose and mouth, and in serious cases, death. Leishmania parasites are found in warm climates such as in India and Columbia but have entered the southern U.S. due to rising temperatures, Greg Matlashewski, a professor of microbiology and immunology at McGill University in Montreal, said. Matlashewski said about 50,000 people die each year from the disease. Those who survive have permanent lesions on their faces and bodies. "The parasite goes into the visceral organs — the liver, the spleen, the bone marrow — and it basically destroys these organs and people die from this infection," Matlashewski said. It especially affects impoverished groups of people — something Dr. Abhay Satoskar, a professor of pathology and microbiology in the Department of Microbiology at Ohio State and co-lead investigator for the research team, said he learned while working during an outbreak of leishmaniasis among Syrian refugee children. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classifies it as a Neglected Tropical Disease because it does not get the same attention and funding as other diseases like malaria. "It makes you realize how privileged we are in this country," Satoskar said. "It's a real eye-opener, to see the suffering and use a different perspective." The new approach to treatment will soon enter the first phase of human trials as the disease, commonly found in tropical regions, makes its way into the southern U.S. "After malaria, amongst the parasitic diseases, leishmaniasis is the second highest in the amount of fatalities or disability adjusted lives," Satoskar said. Satoskar said before gene-editing, the traditional immunization practice introduces a non-weakened Leishmania parasite into the body. This method can still cause a person to contract the disease and have severe symptoms. That is where CRISPR comes in. CRISPR — or clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats — can cut out genes and alter DNA to create a live, weakened parasite that builds human resistance but does not produce symptoms, Matlashewski said. "CRISPR worked beautifully," Matlashewski said. "It only cut out the gene we wanted to cut out." As a result, Matlashewski said, the parasite could no longer cause leishmaniasis. Phase I trials based on the study are expected to start in early 2022, but this can change due to COVID-19, Satoskar said. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "Parasitic Diseases" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment