It is time to meet the "zombie snail," which is somehow even worse than it sounds - The A.V. Club

It is time to meet the "zombie snail," which is somehow even worse than it sounds - The A.V. Club |

| It is time to meet the "zombie snail," which is somehow even worse than it sounds - The A.V. Club Posted: 13 Aug 2019 12:00 AM PDT   As anyone who's watched a few episodes of Planet Earth knows well, the natural world is filled with a seemingly endless supply of biological horror. Weird fish and creepy reptiles coexist with strange parasites and fucked-up bugs, living out their lives in bizarre ecosystems. Because there has to be a silver lining to the fast-approaching destruction of our planet, Wired's Matt Simon has decided to share important details on a real hall-of-famer nightmare creatures: the so-called "zombie snail." The clip shared by Mike Inouye shows this goopy freak in action, but a full description of the unsettling process by which a "zombie snail" is made is important for anyone hoping to alienate their friends in upcoming conversations. As Simon's article explains, the snail is being controlled by a parasitic worm called Leucochloridium. This wriggly little nightmare "invades a snail's eyestalks, where it pulsates to imitate a caterpillar" and "mind-controls its host out into the open for hungry birds to pluck out its eyes." The vore-enthusiast worm then "breeds in the bird's guts, releasing its eggs in the bird's feces, which are happily eaten up by another snail to complete the whole bizarre life cycle." Cool! With a little help from biologist Tomasz Wesołowski—the scientist who discovered that the parasite could actually take control of amber snails a few years ago—Simon goes on to fully explain the rest of Leucochloidium's work. It turns out it "castrates its host," "sends out branches that tunnel through the snail's body," and makes the poor snail's eyestalks appear to dance once it's filled them with "a brood sac full of larvae." In order to get eaten by a bird, the parasite also forces its snail host out into daylight and onto higher branches and leaves. For further horror, consider, too, that birds "don't typically go after snails" so, after eating the parasite-filled eyestalks, they'll leave the snail behind to "not only survive, but...regenerate" their chewed-off bits and "regain the ability to reproduce." Advertisement The entire Wired article is worth reading if you want further details on one of the strangest, most unfortunate creatures in the world. If nothing else, the tale of the "zombie snail" might make all of us feel a bit better about our own lot in life. Debt, relationship problems, illness—how can anything seem so bad when our eyes and genitals are free of parasites and our bodies still are controlled by our own minds instead of nasty little worms? Send Great Job, Internet tips to gji@theonion.com Advertisement |

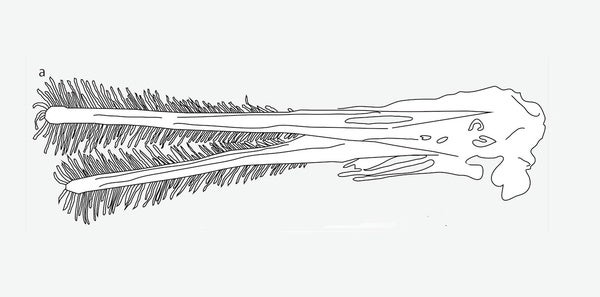

| Sifting through the Pterosaur Menu - Scientific American Posted: 28 Aug 2019 12:00 AM PDT  What did pterosaurs eat? It's a simple enough question, and one that comes attached to just about any restoration of these ancient flying reptiles. We love to see them soar and squabble, but at some point they had to get dinner. But when it comes to direct evidence, the record of pterosaur meals is pretty slim. Gut contents and petrified poop found in association with pterosaur fossils are hard to find, and the fact that many pterosaurs had toothless beaks means we can't have a look at their chompers to make rough insectivore/herbivore/carnivore distinctions. Most interpretations of pterosaur diets are hypotheses that require additional testing – or some fortuitous fossils – to verify. Now a new paper by Martin Qvarnström and colleagues offers new evidence of at least one pterosaur species was dining on. The fossils themselves come from Wierzbica Quarry in Poland. They aren't bones, but instead are a mix of pterosaur tracks and fossilized feces (called coprolites, if you want to get technical) that were deposited in this spot over 152 million years ago. And when the researchers used advanced imaging tech to look inside those fossil feces, they found an assortment of tiny invertebrates that tells us something about what the local flappers were eating. Qvarnström and coauthors found that the coprolites were packed with small, shelled animals called forams, as well as bristles from worms and carapaces from crustaceans, bivalves, and other watery invertebrates. Whoever left the prehistoric poops was subsisting on small fare in bulk rather than loading up on larger entrees, avoiding the Mesozoic carving station and going in for Jurassic tapas. From the abundant tracks found at the same spot, the coprolites were probably left by pterosaurs. What species of pterosaur, though, is another question. There are no body fossils at the site. There's no skeleton to flesh out. But if the feces and the tracks go together, Qvarnström and colleagues propose, then the pterosaur was probably some kind of ctenochasmatid – a specific group of pterosaurs with lots of small, closely-packed teeth that look well-suited to filter-feeding. These pterosaurs were acting like Jurassic flamingos, tottering around and sifting out little morsels from the shallows. It's easy to think of the Mesozoic as a time of aberrations and monsters. Even paleontologists kept this frame of the ongoing reptilian ages for the first half of the 20th century, wondering why scaly oddballs prospered for so long while mammals were waiting in the wings. But something as simple – and even icky – as a piece of Jurassic crap can help us bridge a connection to a world we'll never see firsthand, where something unfamiliar meets part of our modern experience. This is how the Mesozoic world comes alive, science feeding our avid imaginations. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "How do you know if you have worms in your poop" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment