How do you treat parasites

How do you treat parasites |

- Treating mosquitoes may be a new way to fight malaria - Science News

- More promising news about phages, the parasites that prey on parasites - Boing Boing

- The American Society of Microbiology names Bangs a Fellow - UB News Center

| Treating mosquitoes may be a new way to fight malaria - Science News Posted: 27 Feb 2019 10:35 AM PST  The fight against malaria may someday include ridding mosquitoes themselves of the parasites that cause the disease. In the lab, treating female mosquitoes with an antimalarial drug stopped parasites from developing inside the insects. Mosquitoes were exposed to the treatment when they landed on a drug-coated glass surface for as little as six minutes, comparable to how long mosquitoes stop on protective bed nets as they hunt for a meal, researchers report online February 27 in Nature. "People have been exploring ways to control insect pests for an awful long time," says Joshua Yukich, a malaria epidemiologist at Tulane University in New Orleans who was not involved in the research. A strategy that kills malaria-causing parasites in mosquitoes "is pretty exciting." It may be possible to make insecticide-treated bed nets even more effective by adding antimalarial compounds, he says. Malaria, caused by Plasmodium parasites and spread by the bites of Anopheles mosquitoes, is a flulike illness with high fever and chills. Without treatment, it can be fatal: In 2017, there were 219 million cases of malaria worldwide, mostly in Africa, and 435,000 deaths, mainly in children. Since 2000, an international effort to combat malaria in Africa has prevented an estimated 663 million cases, researchers say, largely thanks to insecticide-treated bed nets. The nets kill mosquitoes and help protect sleepers from bites. But that progress has been threatened with the emergence of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes. To test whether targeting the parasites in mosquitoes could work, Flaminia Catteruccia, a molecular entomologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and colleagues treated a glass surface with the antimalarial drug atovaquone. Mosquitoes landed on the surface and absorbed the drug through their legs. The compound then made its way to the insects' gut, where it prevented the parasite Plasmodium falciparum from developing, the team found. The strategy worked whether insects were infected with the parasites before or after the drug treatment. An "autopsy" of the mosquitoes seven to nine days after an infectious blood meal found the insects were parasite free after treatment with certain doses of the drug, the researchers say. Atovaquone, which is used to treat malaria in people, kills Plasmodium parasites by inhibiting a protein in the mitochondria, the energy factories inside cells. But it's possible using antimalarial drugs to treat mosquitoes could result in the parasites becoming resistant to the drugs, endangering crucial therapies. So Catteruccia and her colleagues would like to test other compounds that can kill the parasites in mosquitoes. There are already options out there, Catteruccia says, including antimalarial drugs that have shown effectiveness against the parasites in tests but didn't pass muster as treatment, because of problems with how they were taken up in the human body or other issues. "In a way, we can repurpose drugs that are not good enough for human use," she says. As for the mosquitoes, developing resistance shouldn't be a concern, Catteruccia says. In the study, treatment with atovaquone didn't shorten the insects' life spans or interfere with mosquitoes' ability to reproduce. "The mosquito doesn't care at all about picking up this drug," she says. Along with finding suitable drugs, it would also be necessary to develop formulations that can remain active on bed nets for perhaps a few years, Yukich says. Long-lasting insecticide-treated nets, for example, keep their insect-killing power for three years or so, even with daily use and washing. |

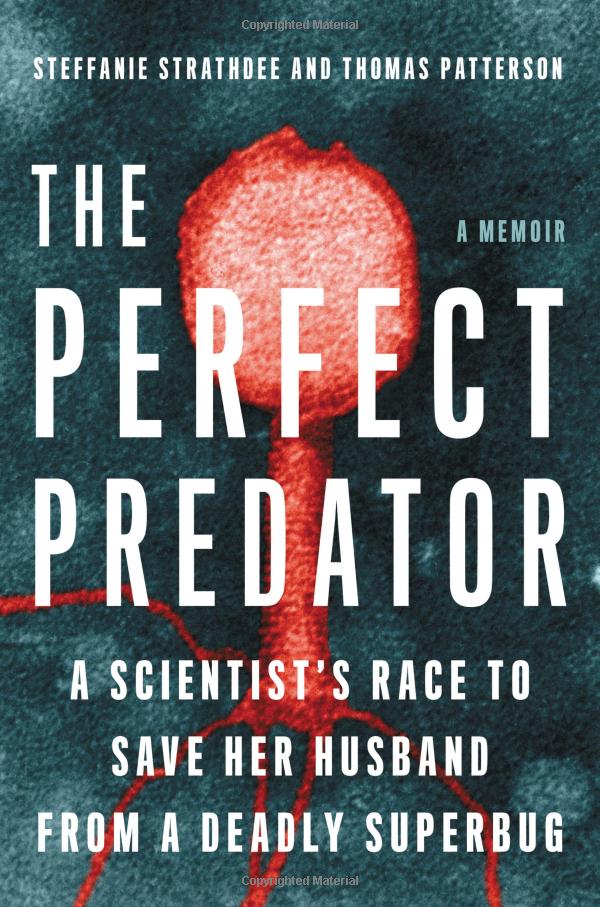

| More promising news about phages, the parasites that prey on parasites - Boing Boing Posted: 26 Feb 2019 01:22 PM PST  For many years, we've been following the research on phages, viruses that kill bacteria, once a staple of Soviet medicine and now touted as a possible answer to the worrying rise of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. Steffanie Strathdee is an infectious disease epidemiologist; she's written a book about her husband Tom Patterson's near-death experience: Patterson was nearly killed by a large ("soccer-ball sized"), infected cyst in his gut, and his life was saved by experimental phage therapy at UCSD medical center. That book, The Perfect Predator: A Scientist's Race to Save Her Husband from a Deadly Superbug: A Memoir, co-written with Patterson, is "one part medical mystery, one part personal memoir," and contains a wealth of accessible material on the potential of phages to treat nascent superbugs. Strathdee and Patterson were interviewed by Wired's Megan Molteni. It's fascinating stuff, and I've ordered a copy of The Perfect Predator after reading about it.

This Viral Therapy Could Help Us Survive the Superbug Era [Megan Molteni/Wired]  TIL: Sharks are attracted to the sound of death metal. Apparently, the "dense tones" of it mimics the "low frequencies of struggling fish." (Damn.) In 2015, a Discovery Channel crew — hoping to attract a large great white named "Joan of Shark" — dropped a speaker underwater and played some. Independent: Desperate to feature the […] READ THE REST The mystery of the glorious fireball emitted by microwaved grapes (featured in my novel Little Brother) has been resolved, thanks to a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in which Trent University researchers Hamza Khattak and Aaron Slepkov explain how they destroyed a dozen microwaves before figuring out that the grapes […] READ THE REST The rise in a belief that the Earth is flat is bizarre and somewhat frightening, a repudiation of one of the most basic elements of scientific consensus. Texas Tech University psych researcher Asheley R. Landrum attended a 2017 flat earth convention and interviewed 30 attendees to trace the origins of their belief in a flat […] READ THE REST If you gave up on playing the piano as a kid, don't despair. Things have come a long way since those drills that had you playing "Chopsticks" endlessly. Take Pianoforall, for instance. This innovative new system lets students play keys right away, learning the structure of the music by playing rhythm-style hits. The 10-hour course […] READ THE REST As big companies wrangle an ever-increasing amount of data, the applications for deep learning grow – and so do the job opportunities. If you've got a working knowledge of Python, all you need are the tools to start making data work for you. Get up to speed on the science and code behind the field […] READ THE REST Anyone who really listens to vinyl knows the medium is far from dead. But convincing others of its appeal can be an uphill battle. For one thing, there's the gear: A quality record player takes up a lot more space than, say, a smartphone packed with thousands of streaming songs at the ready. But here's […] READ THE REST |

| The American Society of Microbiology names Bangs a Fellow - UB News Center Posted: 27 Feb 2019 08:34 AM PST

His research focuses on finding novel pathways to develop drugs that treat African sleeping sickness, which is fatal if untreatedBUFFALO, NY — James (Jay) D. Bangs, PhD, Grant T. Fisher Professor and Chair of Microbiology and Immunology in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo, has been named a fellow of the American Society of Microbiology. ASM fellows, recognized for their excellence, originality and leadership in the microbiological sciences, are elected annually through a highly selective, peer-review process, based on their records of scientific achievement and original contributions that have advanced microbiology. Bangs will be officially inducted into the ASM fellowship at the organization's annual meeting in San Francisco in June. For more than 35 years, Bangs has conducted research on African trypanosomes, single-celled parasites transmitted by the tsetse fly, which cause African sleeping sickness in humans, a fatal, re-emerging disease throughout sub-Saharan Africa. His pioneering research specializes in the biochemistry and cell biology of African trypanosomes and their secretory processes; it has illuminated the biosynthesis and trafficking of key virulence factors in this important human and veterinary parasite. Bangs explained that because trypanosomes are eukaryotic cells, organized similarly to every cell in the human body, treatment of infection is not unlike cancer treatment in that chemotherapy against the parasite has harsh consequences for the patient. However, since infection is invariably fatal without intervention, new, more specific drugs are desperately needed. The goal of Bangs' research is to define aspects of trypanosomal secretory processes that may provide novel pathways to new drugs to treat African sleeping sickness. His research has been funded by the National Institutes of Health since 1994. Bangs has organized the premier international meeting in his discipline—the Molecular Parasitology Meeting at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Mass.—and mentored many microbiology students in his laboratory, and hundreds more globally as lecturer, instructor and director of the Biology of Parasitism course at the MBL. He also served as an ad hoc and permanent member of the NIH Pathogenic Eukaryotes Study Section. He has served on the editorial boards of two of the field's main journals, Eukaryotic Cell and Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. A faculty member at UB since 2013, he was previously on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin where he was a trainer for its microbiological doctoral training program and a member of its Center for Research and Training in Parasitic Diseases. A native of Vineyard Haven, Mass., Bangs received his undergraduate degree in biology from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. He received his PhD in biochemical, cellular and molecular biology from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and completed postdoctoral training in cell biology at Yale University School of Medicine and in microbiology at Stanford University School of Medicine. He is a resident of Buffalo. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "How do you treat parasites" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment